ELS CASTELLS

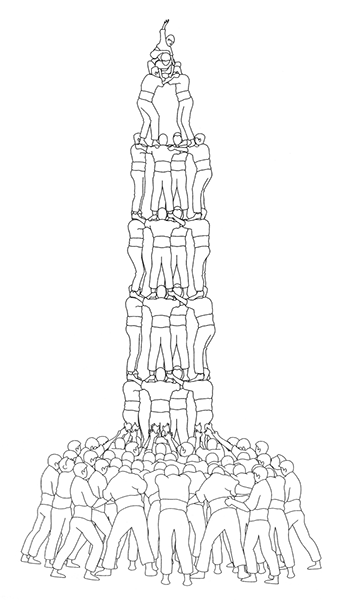

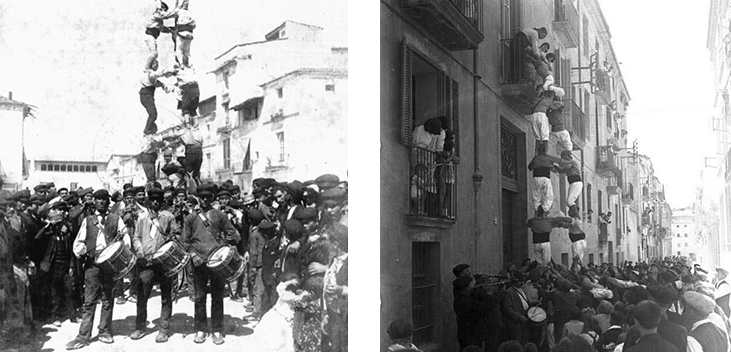

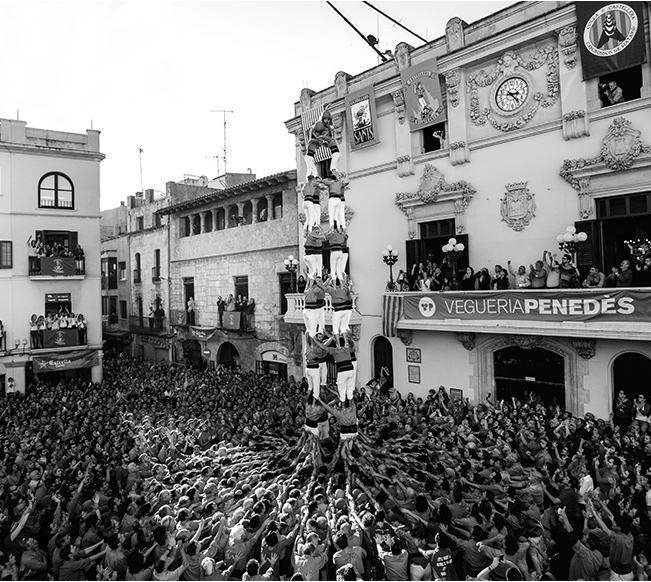

Castells, or human towers, are constructions between six and ten people high that were first introduced in the 18th century in an area called Camp de Tarragona. In the years since their conception they have spread throughout the whole of Catalonia.

Each human tower is the result of universal values such as teamwork, solidarity, self-improvement, the feeling of belonging and the integration of people of all ages, origins, races and social backgrounds.

It is a genuinely Catalan tradition which UNESCO declared Intangible Heritage of Humanity in 2010.

History

During more than two centuries of development, castells have evolved noticeably and they have experienced extreme situations, from being about to disappear, at the beginning of 20th century, to the current best of times.TECHNIQUE

Human towers are not the result of random improvisation in the square, but the fruits, firstly, of a detailed study of the structures, their components, the functions and locations of each of them, and, secondly, of constant rehearsal over many months.

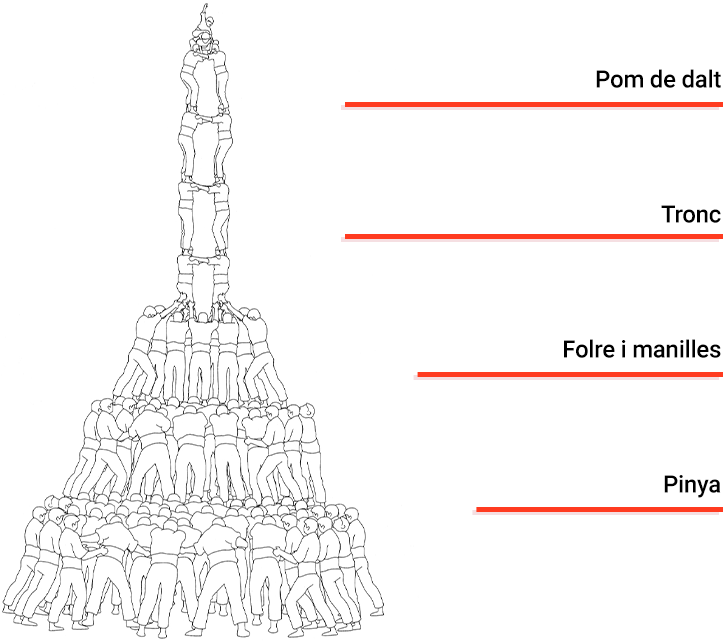

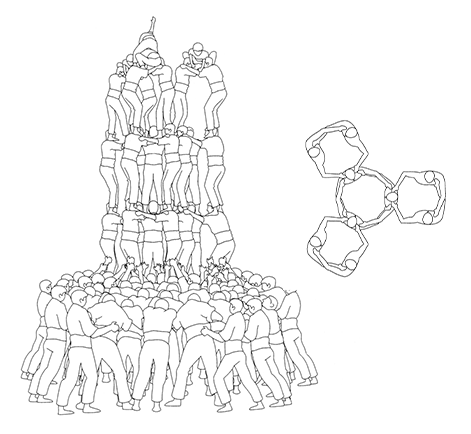

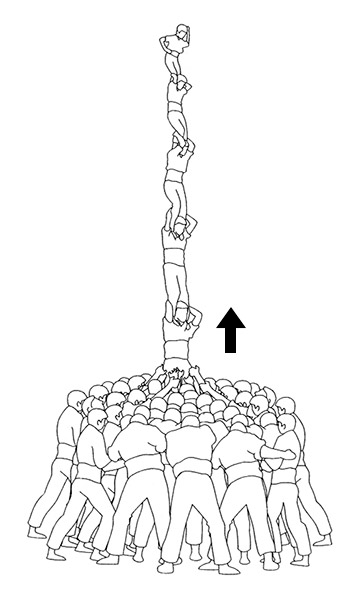

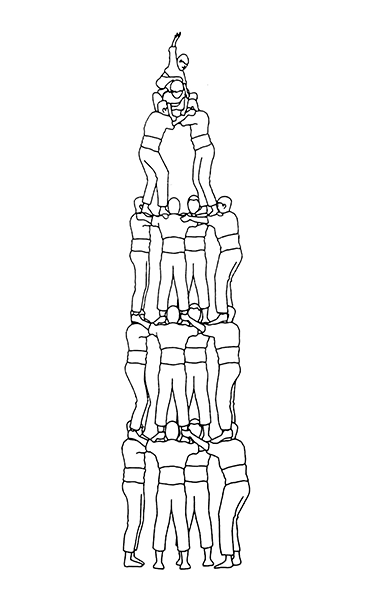

Parts of a Castell

Types of Castell

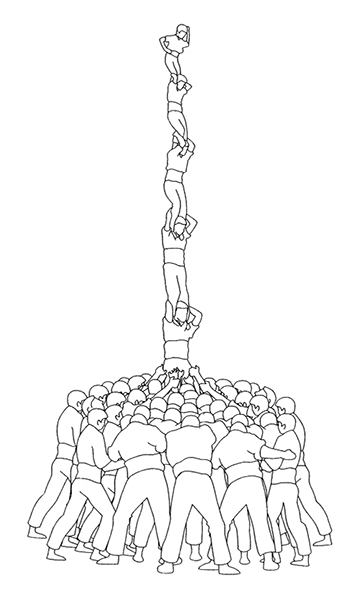

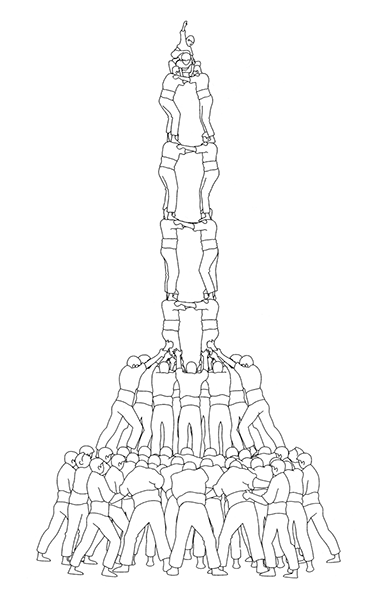

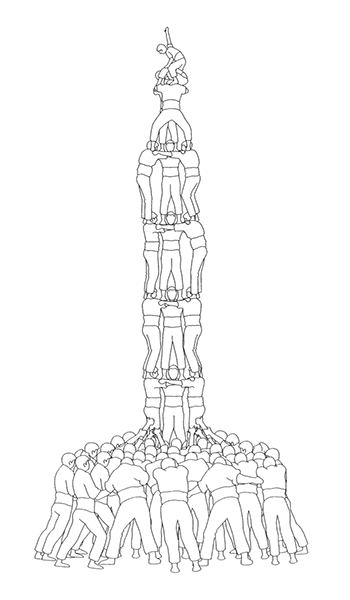

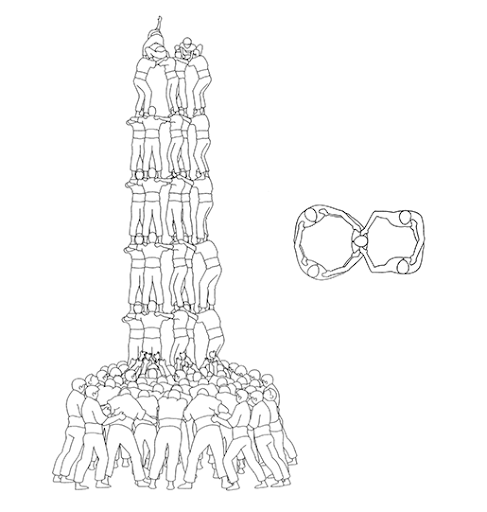

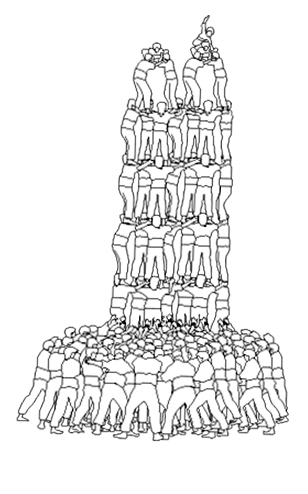

The names of different castells are determined by two parametres: the number of people per level —without taking into account the pom de dalt— and the number of levels. A construction must have at least 6 levels in order to be considered a castell, unless it is a pillar, in which case they must have at least 4 levels.

Simple Structures

These are the easiest to count and identify. They consist of one, two, three or four human tower builders per level. Do not be misled: when we talk about simple structures we do not mean they are easy to make.

Complex Structures

With more than four castellers per level, complex structures are just combinations of simple structures. Some of them are real works of engineering.

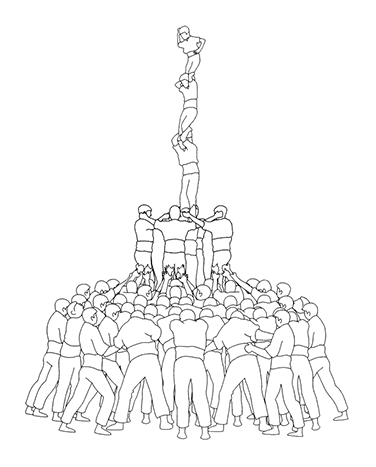

Unique Structures

These are human towers which, despite having a simple structure, stand out because of the way they are raised or because they lack some usual support base.

Illustrations by Xavier Ruiz provided by Lynx Edicions

MUSIC

Castells wouldn’t be castells without the music of the gralles (traditional Catalan wind instruments) and drums, called timbals. The “toc de castell” is the most well known piece of music since it is played while the castellers build the castell. It marks a speed and rhythm for the participants to follow and signals the different phases of construction. Although this toc (tune) is the most well-known, the first tune we hear at any castells performance or event is the “toc d’entrada a plaça”, which plays while the castellers enter the square in which they are to perform. Many other moments have their own corresponding tune, for instance the “toc de pilar caminant”, which accompanies a pillar that “walks”, and the “toc de vermut”, which is played at the end of the performance as a way of closing the event.

THE INSTRUMENTS

The instruments that traditionally accompany castells are the gralla and the timbal.

The gralla seca is a conical tube of wood that measures around 35cm in length and has, with some small exceptions, nine holes: six at the top and one at the bottom, with 2 more at the bell, or mouth, of the instrument which serve to improve tuning and tone. Gralles can be made from different tupes of wood: Jujube, ebony, boxwood or olive, among others.

Other types of gralla include the gralla dolça, a more advanced model than the gralla seca that has two keys at the bottom that allow the instrument to reach a middle F note. The gralla baixa, which is a quarter octave lower than the the gralla dolça, and also has keys, can reach a low A note.

In order to play the gralla a conical tap is added to the top of the instrument, and a reed is inserted into it. The reed is made by artisans out of two pieces of wood tied together with a wire. When the musician blows into the space between the pieces of wood they vibrate and sound is produced.

Generally, musical scores for the gralla are written in G major. Musicians in Sitges, however, refer to the note produced when all holes are covered as D, and therefore they play in a different key. There are two tuning systems used when playing the gralla: 415 Hz, more common in the traditional area, and 440 Hz, more popular in the non-traditional area.

On the subject of drums, Xavier Bayer i Gonzalez indicated in the Vilafranca festival programme in 1990 that “The first drums were made of wood, and in general measured two hands-lengths in height and one and a half across. They had skins at the top and bottom that were tightened using strings; there were also one ore two snares made of gut on the bottom skin that produced the roll sound.”

Nowadays, drums are most commonly made of brass, covered on both sides with natural skin or a tightened plastic, with metal tensors and an adjustable snare on the opposite side. The drum is played with two wooden drumsticks.

History

There are several theories about the origin of the traditional gralla. In any case, what is clear is that its use became generalised between the 18th and 20th Centuries in the regions Camp de Tarragona, Penedès, Tarragonès and Garraf.

By traditional we mean the gralla curta or gralla seca. The gralla llarga de claus, otherwise known as the gralla dolça, appeared in the final third of the 19th Century, allowing players to create melodic harmonies and reach higher pitches. The introduction of the gralla dolça at this time became the object of criticism by a large group of people who preferred, or felt nostalgic towards, the gralla seca. At the same time, there were plenty of people who preferred the gralla llarga, and in fact, this split in opinion has survived to the present day.

The most brilliant stage of the gralla’s history can be dated to the years between 1875 and 1915. At this time the gralla baixa was introduced and the traditional wooden drums were replaced with lighter, brass drums.

From 1915 onwards the gralla became less and less popular as a form of musical instruction in the home as different instruments and tastes in music grew in popularity. As a result, the number of gralla players was greatly reduced.

In 1952 Pere Català i Roca estimated that there remained only 14 grallers, or gralla players, and 7 timablers, or drummers.

In Sitges, in the autumn of 1952, a school was set up in which free teaching was offered for people to learn to play the gralla. In 1969 a similar school was opened in Tarragona and, in 1976, a new band of grallers was formed in Vilafranca.

Also in 1976 the Colla Castellera d’Altafulla organised the first Conference of Grallers “… The simple celebration of such an act represented a step forward in the structuring and formulation of a whole programme of performances in which grallers became fully fledged members of the world of castells” (Món Casteller, Jordi Garcia Soler, 4/12/1976).

Later, in 1981, the Traditional Music Conference was formed in Reus, and in 1986 another was introduced in Guardiola de Font-rubí.

On the 14th of December 1979 the Colla Joves dels Xiquets de Valls presented the group Escola de Grallers.

From the 1980s onwards new pedagogical methods were introduced, and conferences, exhibitions, popular and traditional musical performances were organised, followed by traditional music schools, or aules,which were formed throughout Catalonia in the 1990s.

Since 2006 it has been possible to study the gralla at the Catalonia College of Music (Escola Superior de Música de Catalunya) as a bachelor’s degree, alongside other traditional musical instruments.

The Castell Tune

As Joan Cuscó observes “the Toc de Castells is made up of two parts, used for 3 reasons: the beginning, the crowning of the Castell and the dismount. Both taken as a whole and individually, these tunes describe, or narrate, the process of building and dismantling a castell. It is sound, in this case, which acts as a guide to those who support the castell, so that they know how the construction is progressing:

Xavier Bayer explains that in 7 level castells “when the castellers of the third level climb to their places the toc de castells begins to sound. When the head of the team —the cap de colla— shouts “terços amunt!” —“thirds up!”— the powerful sound of the gralla and the drum cuts through all other noise and make it known the the Castell has begun”.

When it comes to 8 level castells, the toc begins when the fourth level castellers begin to climb, and increases successively according to the height of the castell.

Blai FONTANALS I ARGENTER, Nosaltres, els grallers.

Ivó JORDÀ I ÁLVAREZ, Fitxa tècnica de la gralla. Per conèixer i entendre l’instrument.

Joan CUSCÓ I CLARASSÓ, El Toc de Castells. Història i històries d’una música.

DINSIC (edició a cura de Xavier Bayer i Iris Gayete), Terços amunt! Músiques per a gralla a l’entorn del fet casteller.

LIVE

The human tower calendar changes every year and there are often alterations at only a few weeks’ notice, so the best way to find out when and where you can see castells is to check the performances that are going to take place on a specific date a few days in advance. Bear in mind that human tower activity does not happen all the time, as colles follow a season, although it is unofficial.

WHEN AND WHERE?

Traditionally, this season began on Saint John’s Day (24 June) and ended with the Saint Ursula meeting (the Sunday after 21 October), but this calendar has been extended, and nowadays human towers can be seen virtually all year round, although the time of year with least activity is December and January.

The number of performances has also grown: each year more than 10,000 castells are raised. In the summer, for example, there are dozens of performances every weekend. It must be borne in mind that human towers, like any amateur activity, usually take place at weekends or on public holidays. The importance of the performances varies, although there are some which, by tradition, attract the most spectators year after year.

Just as the calendar has expanded with time, the map has also spread: you can find castells almost any weekend throughout most of Catalonia.

NOT TO BE MISSED

which, due to tradition and the historical results, form the list of dates not to be missed.

THE MOST UNUSUAL

Besides the performances when you can see the biggest human towers, there are some that are exceptional for other reasons: because they have castells at night, because they are held in unusual settings or because they have a particular feature that makes them special. These are just a few examples.

HOW DO THEY WORK?

A typical human tower performance consists of three human towers and a farewell pillar by each participating colla . In each performance there can be one, two, three, four or even more clubs, although the number is normally three. The groups raise their human towers in rounds, following an order of performance that is agreed or drawn before the start. Usually, if the club cannot achieve the human tower it tries to build, it has the right to have another go.

However hard you look, you will never find any written Rules of Human Towers governing the activity. But that does not mean they do not exist: castells are built according to unwritten conventions known and accepted by everyone.

The only performance that does have explicit rules is the Concurs de Tarragona, which basically tries to compile the traditional rules of human towers in writing and apply them, although with some differences.

WHO’S WON?

Although an outsider seeing different “teams” coming together in the same square might think otherwise, castells are not a mere competition, and there are no winners or losers. The colles make the human towers basically to push their own limits and achieve new challenges. That is why it is quite usual for several clubs to leave the square happy after a meeting: all of them feel like winners because they have achieved their objectives.

However, some human towers are clearly more difficult than others. The casteller s , or human tower builders, are aware of this and often, as well as improving their own achievements, they also feel the attraction of performing better than the others. This is especially clear at meetings where clubs of a similar standard or with traditional rivalries coincide.

WHICH HUMAN TOWER IS MOST DIFFICULT?

Unwritten criteria and conventions also come into play in this case. The joy of the human tower builders and the strength of the applause can be a good guide, although if you want an accurate assessment you can use the Concurs de Tarragona points table as a reference.

ADVICE IF YOU WANT TO TAKE PART JOINING THE BASE

Take off your watch, your glasses, your earrings and your rings. If there is a fall these can be dangerous.

Do not raise your head! If you think you will not be able to contain your curiosity, it is best if you watch from outside. Being in the base requires maximum concentration.

Let the gralles , the shouts of the cap de colla —the leader or head of the club —, and the ambient noise guide you on the progress of the human tower.

Push with your chest rather than your stomach, and only when you are asked to from the front. When you hear “Dóna’m pit!” (“Give me some chest!), you will know it is time to push.

Take advice. Everyone has had a first time and those with more experience will be delighted (sometimes only too delighted!) to tell you what you have to do and how to position yourself.

If there is a fall, do not bend down and carry on pushing forwards.

Enjoy the experience. You are bound to want another try!

Values

Human towers have been recognised by UNESCO as Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity since November 2010. Their aesthetic value and defiance of gravity certainly had something to do with this, but the main reason for their recognition was provided by the values implicitly involved in castells.

TRADITION AND MODERNITY

Castells is an activity that, in large part, remains true to the spirit and customs of the teams of 200 years ago: being an integral part of the local festival, the musical accompaniment, and the classification and denomination of castells are just a few of the elements that have been passed down from generation to generation. This well of tradition does not imply, however, that human towers haven’t been able to change and adapt over time. In fact, it is the activity’s capacity to change and adapt that explains castells’ unrivalled persistance and vitality today.

The changes are both technical and social; take for example the incorporation of women into the clubs that began in the 1980s. Furthermore, castells have been the subject of numerous scientific studies that aim to improve the security of the participants. Thanks to these investigations, a protective helmet was designed to safeguard the youngest castellers. Human towers have also become more noticeably present in the media, particularly on the Catalonian channels of Televisió de Catalunya, which has supported castells to such an extent that it has used them to showcase its technological innovations such as, for example, 3D film.